Five artists and curators respond to the question “Who is your work for?” as prompted by Kate Gilbert, Executive Director of Now + There for the second part of a four-part series Art in Service with Big Red & Shiny and Alter Projects.

Each day that you and I choose to venture outside of our dwellings, we navigate streets, sidewalks, and other public infrastructure made not by us, but for us by other people who, assumedly, had our best interest in mind when creating them.

How many times have I thought, “That idiot, I bet they don’t even walk!” about a depersonalized traffic engineer as I wait to cross four lanes of deadly traffic?

Design may be the most straightforward example of a creator-user relationship, and perhaps the easiest to critique. It works, or it doesn’t. For me. (Note, that highway works perfectly for the drivers speeding along.)

Could it be just as easy to evaluate socially-engaged artwork if we look at it through the same lens: who it is for? With this in mind, and picking up the thread from the conversation in Part 1 of Art in Service with Maggie Cavallo and Leah Triplett Harrington, I asked five artists, curators and activists the simple but complicated question, “Who is your work for?” and asked them to respond via a shared online document and engage in conversation.

Che Anderson, Jennie Carlise, William Chambers, Elisa Hamilton, and Lori Lobenstine gave answers as genuine, complex, humorous and generous as their work. From dedicated practices that give voice to others, to works that are calls to action, the following conversations and statements debunk any hopes I had of trying to simplify the practices of artists working with the public. Thus I will continue walking the streets trying as best I can to see the point of view of the automobile driver and the pedestrian. In other words, to leave open room in my critique to accept and embody as many audiences as possible and to believe that everyone, from the artist to the engineer, has the audience’s best intentions in mind. Even if I have to wait five minutes to cross the street.

– Kate Gilbert

“Who is your practice for? ...You all come at your practice of art-making, curating, and instigating change from different angles, and we’d love to know who you do your work for – is it for a specific audience, the general public, or yourself? Not sure? Don’t care? You can answer the question in any way you choose.”

Elisa Hamilton: My practice is for all of us. As my work has developed over the years, inclusivity has become a guiding factor in the projects that I take on and the work that I create. Dance Spot was the first project that really identified that foundational need for me. That project has had a longevity that I never imagined when I first created it in 2012, and I think that's because it's a project that is rooted in bringing people together to have a joyful experience. The exhilarated, buoyant feeling you get when you are dancing is something that we all understand, and even those who prefer not to dance take joy away from watching others do so. Those first moments of dancing with strangers on the sidewalks of Fort Point were some of the most enlightening experiences that I've had as an artist. After creating that project, I knew that I wanted to focus on making work that goes beyond being accessible, and is welcoming to everyone. My most successful projects, like Dance Spot, are the ones that bring lots of different kinds of people together in generosity, sharing, and joy.

Elisa Hamilton, Dance Spot, Summer Street Bridge, Boston, MA, 2012. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Elisa Hamilton, Supermarket Products, 2015 Photo: Michael Blanchard

William Chambers: I am interested when you write that you aim to make art : “…that goes beyond being accessible, and is welcoming to everyone.” In my own practice, I am constantly asking what can art do and what are its limits? You have had many successful projects and have been doing this for some time now. I would love to hear how your view of the power of art and its potential has changed or is changing. What is the beyond for you?

EH: Back when I was an art student I remember arguing with one of my professors that art really could change the world. I felt so sure of myself at the time (oh to be 22 again!), but I realize now I was also scared- because if art couldn't change the world, then why had I chosen to devote my future to it? In the following several years, especially as a new graduate, I grappled with what my work had to offer to the world (and sometimes still do), and if it was really possible to make a difference.

Before I went to school for artmaking, I had been working towards a degree in theater. One of my biggest takeaways from acting is that the best actors are generous actors- they make the scene about their partner rather than about themselves, and that's when the real magic happens. I think my art started to become much more successful when I began to put the primary focus on the participant rather than the creation of the art. Art has its limits, but having the ability to manifest a positive, meaningful, resonant experience with participants is a powerful thing. Creating that cycle of generosity; if art can change the world, I think that's how.

William, your work has a beautiful thoughtful and generous quality to it; do you see the work you do as having a ripple effect in the world?

WC: Thank you for your response. It is so great to be having this conversation. I hope for a ripple effect and I catch glimpses, but maybe we can never really know where our art touches. I totally agree that my practice got way more interesting when I started to make work that was more about creating a space for others and much less about me. Maybe this is not the space, but I would love to know more about how the Supermarket conversation project turned out. It sounds like a lovely premise of gathering stories of generosity and greatness from neighbors.

EH: Supermarket definitely was a project that was propelled by thoughtful public participation. I asked the questions, but the products were developed directly from public input. I never could have imagined how rich the conversations would be, or how clearly the data would emulate the kindness that still exists in our world, even though sometimes things can seem so grim!

Lori Lobenstine: When I think about my work with the Design Studio for Social Intervention (DS4SI)—and I rarely think about it as my individual work—I think about it as having many roles and many audiences. I think activists are the biggest part of it for me—people who care deeply about social justice and who are looking for (or just needing) new ways to think about their work and bring about change. I picture the young Appalachian crew we worked with this year, who came alive when they were figuring out what Southern powerhouses like Dolly Parton and Pat Summitt would bring to the challenges they were facing. I think about activists—young and old—who teared up when they saw our Black Citizenship Project video, seeing in the artists’ work a new way to take on state-sanctioned violence against the Black community. I think about the many activists who have read our Spatial Justice paper or Social Emergency Procedures and reached out, grateful for a new frame that made something make sense in a new way.

Design Studio for Social Intervention, Black Citizenship Project, 2015. Photo courtesy of DS4Si.

I also love our spatial justice inspired creative placemaking work. Often the audience is just regular folks on the street, which is really refreshing. For example, in our work of creating “productive fictions”, we create glimpses into what might be in the world we want, and build micro-spaces where that world already exists. These productive fictions create room for people to jump off our ideas and imagine new possibilities. To see folks stop their daily life and suddenly be totally IN something new, like the Public Kitchen, is really fun. And the way some folks just run with it—bringing it to their own neighborhoods or making it even better in a so many ways…I love it.

Design Studio for Social Intervention's Public Kitchen invited Upham's Corner and Dudley Street residents to feast, learn, share, imagine, unite and claim public space. Photo courtesy of DS4Si.

Finally, my art is for my parents—two amazing old school activists who just love any new idea I have.

EH: Hi Lori, I loved reading about your work (here and online!) and about the deep influence that your family has had on the work that you do. Did you always know that you would follow in the footsteps of your parents as a force of change, or was there a particular moment of significance that brought you to this place?

LL: I thought I was going to be a sports photographer, then an architect, then a basketball coach. Then again, my parents were activists while they were post office workers, social workers and inn keepers, so…I could have done it all =) But for significant moments, let me share a humorous one and a serious one. In college I got arrested doing a sit-in to protest Wesleyan’s investments in apartheid South Africa. Afterwards, my dad sent me a faux-fancy handwritten card that said, “Mr. and Mrs. Geoffrey Lobenstine are proud to announce the first arrest of their daughter, Lori Lobenstine”! On a more serious note, tomorrow I will commemorate the first anniversary of my mom’s passing by doing an installation at the World Social Forum, which she would love.

EH: Your parents sound like incredible people, and the World Social Forum seems like the perfect place to commemorate your mom's passing, with others who want to build a sustainable and inclusive world!

William Chambers: My practice is for Justin, a homeless kid with a dirty face who roller skated up to the Service Station in the York Public Library and told me safety was missing. I helped him embroider a gun in black thread with a banned symbol over it. It is for Virginia, who spent several hours embroidering “Motherhood” on the towel in precise purple stitches as she told me about her young daughter in Baltimore and how she was staying in the homeless shelter, but got to see her on weekends. It is for Grace who at 90 can no longer embroider, but could tell me exactly what I was doing wrong. For Anthony a middle aged man who asked me to embroider his deceased wife's initials because “she was the love of my life.” It is a chance to listen to those who often do not have a voice and to create a space for shared communication and documentation of all kinds of people with multiple life experiences. And on a bigger level it is the radical argument that work embedded with the stories and touch of many hands can hold its own against the art canon. As artists we gain when we step outside ourselves and use our tools in the service of something beyond us. It is a chance to cross, briefly, the social barriers that limit and stunt the kind of conversations we long to have and is worth the risk. My hope is that this practice can lead to greater understanding and empowered action. It is for others and for me. It is about Service.

William Chambers, Service Station, 2016. A traveling interactive embroidery project with attendant; 300+ participants and travelled to 10 cities. Photo courtesy of the artist.

William Chambers, Spaceship York, 2016. An interactive community installation where collected dreams were sent to space, York, PA. Photo courtesy of the artist.

LL: William, one thing I love about Service Station is the pace. How do you look at time–either in terms of the time spent with others embroidering or the throwback aesthetic and craft of Service Station–as part of your medium?

WC: Time seems super important to what Service Station is doing. Embroidery is a practice of speaking slowly because when you speak with a needle, you have to take care and really think about what you say. That slowness is absent from today and I wonder if we can reclaim it from our pasts? Many people say they used to have time to embroider when they stop at the Service Station. I had never embroidered before this project and have found it to be peaceful and calming and also intimate. We now think of time as an economy to be added up and itemized. Committing to this extended project where the time spent could not equal the funding sources was possibly an act of resistance, but also trying to shift my own thinking and allow others to as well.

Che Anderson: My practice is for the individual with a story to tell and no one to tell it to; who prefers to place their passion, energy and ideals onto a public canvas, choosing to scream their observations, praises or disdain to the masses rather than whisper it to those deemed influential or important. It is for the person that never let society, or mom and dad for that matter, tell them drawing on walls is inappropriate. It is for the young person that enters an institution of fine arts unable to find something they can relate to, and so they feel as though art simply is not for them. My practice is not about fame, or money, or admiration, but is performed for the community, the underrepresented and the underappreciated. The goal is to initiate dialogue and curate a conversation about the utilization of public space, the everyday lives of the native population, and the interaction between private institutions and the general public; one must understand the social constructs of their surroundings before attempting to change, beautify, or further develop, and it is my belief that I can assist in that dialogue. Caleb Neelon, a Boston-based artist, speaks often about the importance of communication, and his ability to reach beyond his believed demographic due to this skill. It is my hope that I too can serve as a conduit for furthering the discourse about public art to an even greater population; after all, that is whom I do this for.

Alice Mizrachi, Mother, Maiden, Crone, 2016) in Downtown Worcester. Photo: Che Anderson

Jennie Carlise: Hi Che, I enjoyed reading your post and getting a better sense of what you are working on via the internet world. The question that I have for you is somewhat similar to the one that you’ve posed of me. I would love for us to talk more about the delicate issue of your role in understanding vs. changing a community through public art. To start with, what’s an example of the way you’ve negotiated this?

Damien Mitchell, Untitled, 2015 adorns the Hanover Theatre in Worcester’s Theatre District. Photo: Che Anderson

CA: Hi Jennie, I've found that the best way to navigate understanding vs. changing a community through public art is to realize that the two thoughts aren't mutually exclusive. The only way to change, influence or enhance a community is to first understand it; to gauge what is deemed appropriate by navigating the boundaries within the community and then seeing how you can push those boundaries. Our first City of Worcester Public Arts Working Group mural was vibrant, colorful and contained an abstract narrative that caused slight confusion in the community. I loved it! Reactions ranged from praise to complete disdain and a call for it to be removed; not because it was obscene or vulgar, but because people “didn't like it”, which is great! It stirred conversation. Our next mural was much less colorful and featured a profile of a woman, which was much better received by the General community, but the point wasn't to appease people but rather to provide something different. For me that is most important: representing different voices in the community, from the loudest and most influential to the near mute individual getting through life as an unknown constituent. Only by engaging as many audiences as possible can we truly navigate what it means to understand and change our community.

JC: There’s really nothing like working in public art to remind you that art still matters. Thank God, people care enough to not like something and call for its removal. So much cultural work happens through the community conversations around a piece once it's installed. What kind of boundaries have the murals you’ve created pushed? Have you ever felt that the wrong boundaries were being pushed?

Jennie Carlisle: For the past three years, I was a curator for Elsewhere, an artist-run residency program operating out of a former thrift store in Greensboro, North Carolina. It is a blended studio, living, and exhibition space supporting new art commissions and dynamic public programs that invites communities into the museum as co-creators. As a curator for such a unique enterprise, I produced complex event based programs, such as Southern Constellations and South Elm Projects. These programs were shaped directly in response to questions about who they were meant to serve, what my role was in connecting various communities together, and how Elsewhere could support broadly inclusive conversations on a host of contemporary issues. Each program served a very specific set of people, and I understood my work as being for them.

People hopping through downtown Greensboro, NC for Agustina Woodgate's Hopscotch, as part of Elsewhere's 2015 Curatorial Initiative, South Elm Projects. Photo courtesy of Elsewhere.

Still, I can offer a few broad reflections on what I’ve learned through this experience about the overarching drive for my curatorial practice. I work for artists, for my home institution, and with a range of different communities simultaneously – mostly I work for folks involved in making things together and then for visitors to a project, but I also think about connecting to spectators and colleagues further afield and to funders, of course. I work for people with something at stake, for the experts on a subject and for all of us feeling our way through new territory. I work for dreamers of better futures and beautiful things, for curiosity, for people taken by surprise, for people who care that what we are making Art, and for people who don’t know that it is. I do this because I like finding ways to knit artists, audiences and participants together into novel compositions, and because I like being the glue of a project and all but disappearing into what we’ve made together.

CA: As an individual that also helps to facilitate art in public spaces I often find myself questioning if it's more important to curate work the community will be content with, or to provide content that will cause them to delve deeper into their personal ideology and feel uncomfortable enough to stir conversation with a neighbor or random passerby; how do you handle that choice, and which is more important to you?

JC: When it comes to creating projects for public spaces, so far we (the staff at Elsewhere + I) have focused mostly on projects with a convivial spirit and a friendly, approachable facade. This felt right for our relationship to our community, and in keeping with Elsewhere’s reputation for playful engagement and creating space for curiosity and openness. Any of the South Elm Projects are examples of this, and particularly Agustina Woodgate’s Hopscotch, Samara Smith’s On Hamburger Square, and Camp Little Hope’s Chamber of Commons.

I don’t think that producing art that is comfortable to be a part of is necessarily in opposition to critical engagement. In fact, it can be quite the opposite, allowing participants to stay open to a process and placing them in a mode where they feel safe exploring new ways of thinking and acting with other people. Creating a space where people feel that they can be vulnerable and take risks with their neighbors is a powerful thing. I learned this lesson from several projects in the past year. For Carmen Papalia’s Blind Field Shuttle, the artist (who is blind) led eyes closed walking tours of the city, which allowed participants to reflect on the problematic degree to which urban spaces are organized for visual navigation. The tours were certainly fun to take part in and captured the attention of a wide variety of people (from local business owners to the city’s urban planners). Heather Hart and Jina Valentine’s The Black Lunch Tables, was a similarly inviting and thought provoking project – providing a platform for intimate conversations around issues facing the Black community and Black artists more specifically. The conversations themselves were not always comfortable for people to be in (because they required folks to share in ways we’re not always used to and to divulge messy thinking on complicated issues), but I think the success of the project was really in that it created a safe, interesting space for people to talk to each other in.

All of this said, I do believe in pushing the boundaries for what people understand as public art whenever possible, and in staying aware of the social possibilities of whatever project you are working on. Murals and sculpture can be great for a community, but other forms are often more effective in producing direct community interaction and dialog, and for me, that’s what it’s all about.

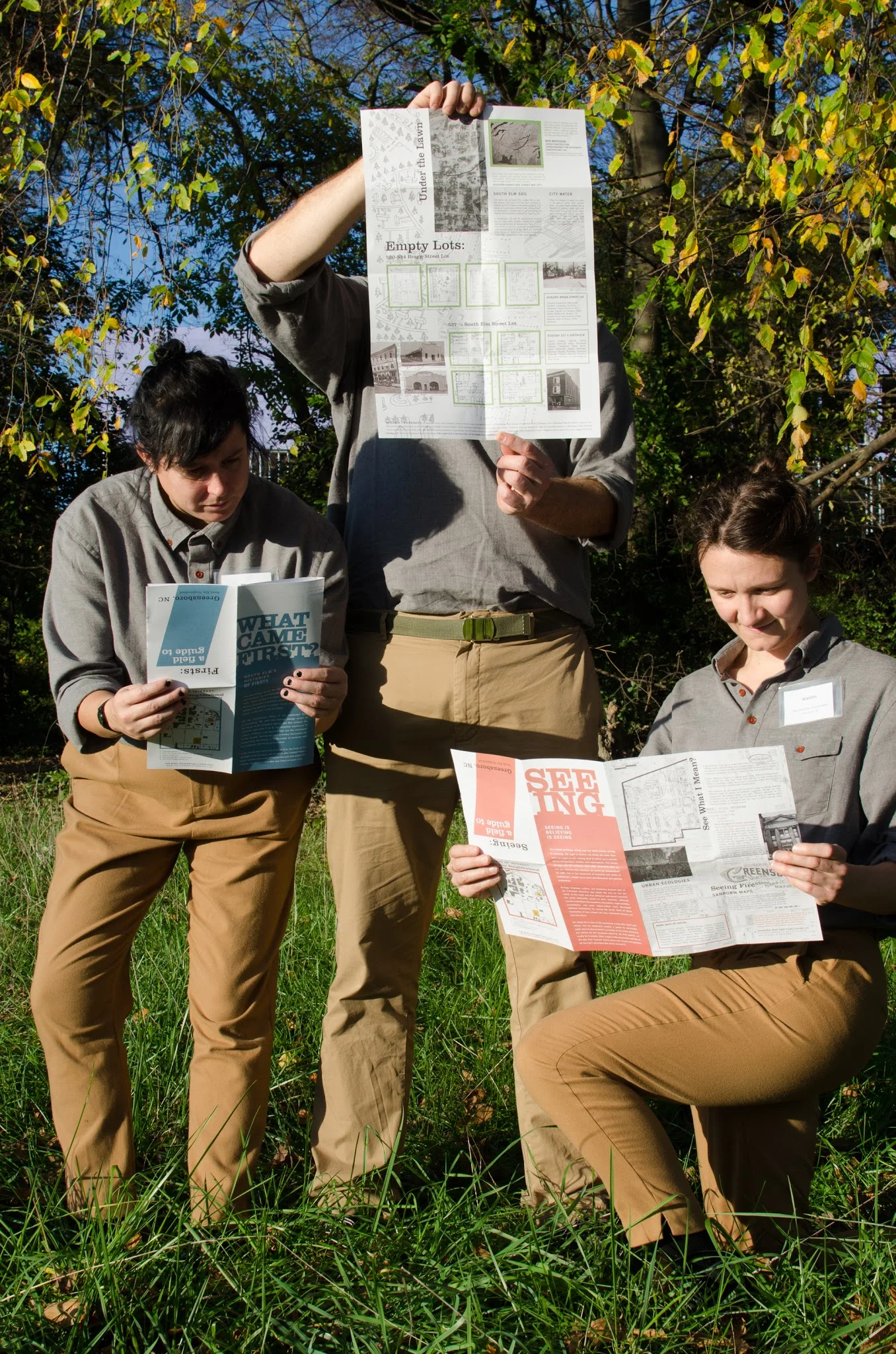

Camp Little Hope as The Chamber of Commons with their neighborhood field guides for Elsewhere's 2015 Curatorial Initiative, South Elm Projects. Photo courtesy of Elsewhere.

Discussion among Greensboro artists for Heather Hart's The Black Lunch Tables, as part of Elsewhere's 2015 Curatorial Initiative, South Elm Projects. Photo courtesy of Elsewhere.

About the contributors:

Che Anderson – Art instigator and street art affectionate, Che Anderson is a project manager at the Office of the City Manager Edward M. Augustus, Jr. in Worcester, MA. Anderson is breathing new life into the streets by commissioning murals and participating in an art master plan for the City of Worcester. Anderson is currently orchestrating Pow! Wow! Worcester, a ten-day festival-style celebration opening August 26 with 10 murals, artist panels, and outdoor celebrations to strengthen community engagement and regional tourism.

Jennie Carlise – Jennie Carlise, independent curator and art historian based in central North Carolina, is dedicated to socially engaged curation, collaborative processes of art production and situation driven aesthetics. From 2013 to 2015 she was the Program Curator at Elsewhere Museum in Greensboro, North Carolina – a living museum, ever changing three-floor art installation, and artist-residency program dedicated to cultivating process-oriented, context driven art practice. For Elsewhere, she oversaw the production of 150 new art works for the museum and developed public programming to bring audiences into art production processes. Carlisle’s projects take form through exhibitions and artist residencies, parties, platforms, systems creation and schools.

William Chambers – William Chambers is a socially engaged artist based in the United States. After 20 + years of art making, and teaching he has just completed his MFA at The Massachusetts College of Art and Design. His work has been exhibited nationally in art museums, galleries and on street corners. Whether embodying the destruction of the home, rethinking dreams and urban decay, or asking the question "What's Missing?", William dissects complex issues in his interactive installations. The audience becomes his partner on a journey of discovery. Humor, sleight of hand, raw emotion, and explosives are tools in William’s arsenal. His current work in Boston, Service Station, asks the question, “What is missing in the world or your life?”

Elisa H. Hamilton – Elisa H. Hamilton is a multimedia artist whose practice focuses on the creation of inclusive artworks that emphasize the inherent joy of our everyday places, objects, and experiences. Her ongoing project Dance Spot has engaged with a variety of communities in Boston, as well as at the DeCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Hamilton has been the recipient of four public art grants to create temporary public works in Boston's Fort Point neighborhood. She was the 2016 Spring artist in residence at the Boston Center for the Arts, where she developed her project Supermarket, exploring the concept of a neighborhood store for superpowers. She is currently exhibiting Lines and Vines, a solo exhibition at Boston Children's Museum Art Gallery, and touring Lemonade Stand, a traveling interactive art installation with fellow artist Silvia Lopez Chavez. Hamilton is a graduate of Massachusetts College of Art and Design (‘07) where she now serves on the Board of Trustees.

Lori Lobenstine – Lori Lobenstine, Program Design Lead at ds4si, grew up in a family of community and union organizers, and decided early on that working with youth was her passion and her route to creating change. She has been a youthworker for the past twenty years, in settings as diverse as classrooms, basketball courts, museums and foreign countries. Throughout these experiences, she has struggled with the challenges of creating new designs with youth, in fields that are often top-heavy and funding-driven. As a life-long activist, she is inspired by the vision that new design tools and a greater design awareness will bring new energy and power to our work. Lori was also the founder of femalesneakerfiend.com and author of Girls Got Kicks.