Above Photo of Liz Glynn: Open House in Kenmore Square by Ryan McMahon

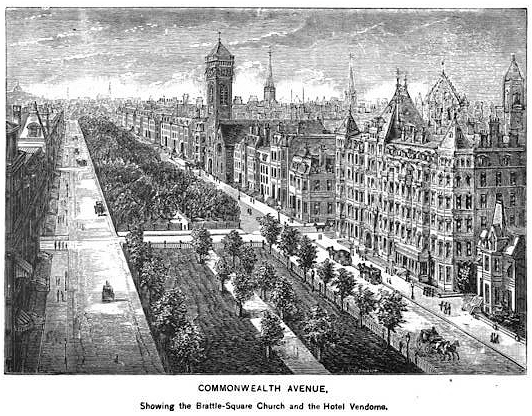

Header photo: Commonwealth Avenue and the Back Bay c. 1872 courtesy of Boston Public Library & Boston Landmarks Commission

The Commonwealth Avenue Mall near Kenmore Square is classic Boston. This sliver of green space on the Comm Ave median is lined with iconic 19th century Back Bay brownstones. It’s a stone’s throw away from Fenway Park. It’s practically bathed in the neon glow of the Citgo sign. And now, it’s the site of Liz Glynn:Open House, Now + There’s latest public art project. But not only does this slice of parkland provide an ideal setting for contemplation in an open-air ruin of a ballroom -- it also has a fascinating origin that enriches the Open House’s potent message.

As I discovered, the history of the Mall closely mirrors the history of Boston: a history of a city physically remaking itself, of the contentious legacy of public planners striving for social equity, and the ongoing struggle for truly democratic public space.

The Commonwealth Ave Mall was among Boston’s first planned public spaces. True, Boston had already established the importance of green space with the Public Garden, an immensely popular Victorian-era development. And the Boston Common, initially a utilitarian space, had evolved in its usage to become the oldest city park in the United States. But when construction on the Mall began in 1856, it signalled the very beginning of an urban planning renaissance in the city that lasted through the Gilded Age (1870's - 1900).

Like many cities in the 19th century, Boston was facing the twin crises of pollution and overpopulation. Boston’s political leaders and urban planners viewed the built environment as an important tool for mitigating the city’s environmental problems. In this city on the precipice of redefining its natural landscape, Arthur Gilman, architect of the Comm Ave Mall, was laying the groundwork for a new one.

Gilman’s design for the Mall envisioned a 32-acre strip of green space running through the nascent Back Bay neighborhood. While construction on its eastern portion began before the Bay was filled, the rest of the Mall was constructed concurrently to the massive landfill project that created the Back Bay neighborhood. The Mall was completed in 1888.

Gilman, planning the Mall, took inspiration the elegant tree-lined boulevards of Paris. He envisioned the Mall as a space intended to promote health and wellness. As the Back Bay Commission reported, the Mall existed so that “a reservoir of pure air may always be supplied from the ample sources of health and freshness outside the city limits.” It was also designed to accommodate strolling, a popular 19th-century recreational activity. It allowed residents of Boston’s newest, wealthiest neighborhood a respite from the crowded, polluted city around them.

Indeed, among 19th-century social revitalization efforts, parks, in particular, held the promise of alleviating social ailments of the day; pro-park rhetoric blended the intersecting discourses of class tension and sanitation to assuage perceived environmental and social disorder.

Take the words of Andrew Jackson Downing, the father of American landscape architecture, who believed that “the higher social and artistic elements of every man's nature lie dormant within him, and every laborer is a possible gentleman, not by the possession of money or fine clothes, but through the refining influence of intellectual and moral culture.”

Or, Frederick Law Olmstead, who believed that urban green space could “inspire communal feelings among all urban classes, muting resentments over disparities of wealth and fashion.” (His famed Emerald Necklace, built in the 1870s to connect the Boston’s parks, is the site of another newly opened public art installation this fall, Fog x FLO: Fujiko Nakaya on the Emerald Necklace.)

At a time when contemporary observers decried the mutually constituted social ills of immigration, industrialization, and pollution, 19th-century planners saw a solution in urban green space. They sought to socialize the city’s public to the values of the wealthy classes. Uncovering this facet of urban history complicates the notion that outdoor city space is inherently more egalitarian than privately owned property like shopping malls. It lends a richer understanding of our shared public space and uncovers novel interpretations of Open House.

Glynn’s piece reflects the grandeur of a long-demolished interior, meant for the enjoyment of the wealthiest class and now open to all. Its position on the Commonwealth Ave Mall interrogates the values of an ethos of urban development that sought to both sanitize and pacify while envisioning a more democratic use of space.

Photo of Liz Glynn: Open House by Dominic Chavez

Today, ensuring equitable access to public space continues to be contentious. As Glynn stated, the outcry in the 1980s over the state of New York’s parks made her call into question the ways in which we police the use of open space. So we must ask: for whom was public space like the Commonwealth Avenue Mall designed? Whose values did these parks reflect, and how can we move forward as a city while remaining cognizant of our past?

Public space evolves, always responsive to a changing public. It is not the victim to the whims of 19th-century Brahmin architects. Highways become greenways. A public art installation can reimagine an underutilized section of a historic public promenade, reflecting on its past and re-imaging its future.

Works cited:

Puleo, Stephen. A City So Grand: The Rise of an American Metropolis, Boston 1850-1900. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2011.

Taylor, Dorceta E. "Central Park as a Model for Social Control: Urban Parks, Social Class and Leisure Behavior in Nineteenth-Century America." Journal of Leisure Research (1999), Vol. 31, No. 4, pp. 420-477.

"The Mall." Friends of the Public Garden. Accessed August 11th, 2018. <https://friendsofthepublicgarden.org/our-parks/the-mall/>